playbooks

Code Strategy

We are biomedical data scientists who use code to answer biological hypotheses and explore biological data. It is therefore important to define how we use, write, and share code.

1. Using code

Code is ubiquitous on the internet, and there are many examples of both elegant and useless code. We leverage all possible resources to achieve our goals; using both trusted software and validated code snippets where available.

We use trusted software wherever possible, selecting to use code that is tried and true, with a strong, active community. When we use these software packages, we specifically take note of which version we’re using, as different versions of different software have different functionality, and often induce different results.

We indicate and track these versions in environment files (for example, here). When we write papers, we are also conscientious to cite all pieces of software we used in our analyses.

We also often use code snippets that we identify in Stack Overflow, github gists, package tutorials, other codebases in the lab, or other sources. These pieces of code present examples on how to perform specific tasks, and we typically use them through some combination of copy+paste+modify. When “borrowing code”, we make sure to specifically cite where we derived this inspiration from, using in-line comments (for example, here). We are cautious in using these examples, validating that they work specifically for our use-case.

Most of the time, it is safe to assume that all code you can view publicly can be used freely.

However, we are also aware that certain licenses might exist that prevent us from repurposing other people’s code.

We must look out for these exceptions, and steer clear from using code with restrictive licenses.

However, if you must include code from a repository under a restrictive license you can either change the license or modify adapted code substantially to avoid conflicts.

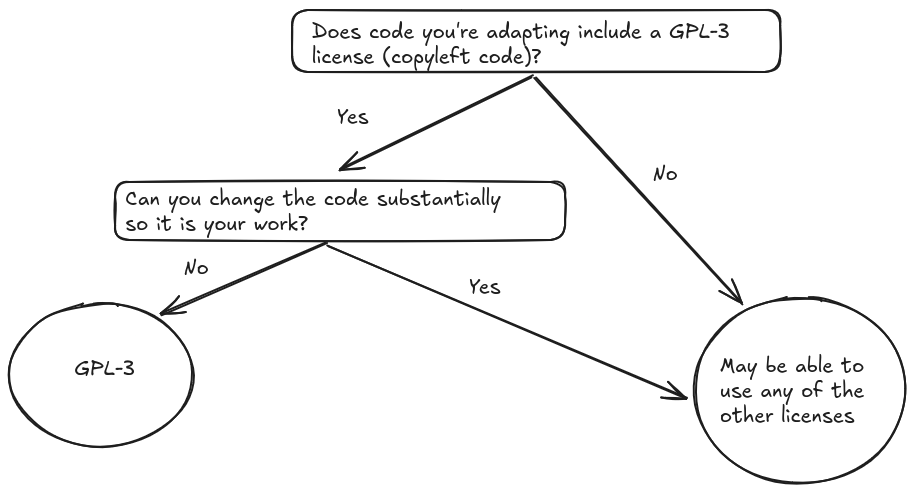

The following flowchart demonstrates the decision process if the adapted code is licensed under a GPL-3 license:

2. Writing code

We take pride in the code we write. All code we produce should 1) work over and over again, 2) be easily understood, 3) be well organized.

1. Code should work over and over again (repeatable)

Good code is repeatable. Running the piece of code should return expected results today, tomorrow, next month, and next year for anyone who runs the code (especially you!). This means specifying software versions in an environment file (or docker image), setting random seeds (where randomization needs to be avoided), documenting input and output data-specific formats, and version control (for both data and code).

2. Code should be easily understood (readable)

Good code is readable. Based on the logic, variable names, and documentation, anyone (especially you!) should be able to understand what your code is doing. Readability also means standard formatting. We always lint our code, and use automatic formatting wherever possible (e.g. python black). We use pre-commit hooks to ensure our code follows conventions before committing.

3. Code should be well organized (maintainable)

Whether a software project, data analysis project, or data project, you must organize your code in a deliberate and meaningful way that maximizes maintainability. All projects continue in some fashion, and the repositories we make should be maintainable for long periods of time. We will walk through each of the three types of code projects in more detail below, but each of them have standard organizational design patterns that, if followed, will maximize longevity.

4. Waylab Specific Conventions

:exclamation: Waylab Specific: This may not apply to other labs!

Waylab code should (usually) follow these conventions for readable, functional code. Note that these conventions will change as the field of biomedical data science evolves and improves.

- Use formatted string literals (f-strings) to concatenate or insert information into strings.

- Use pathlib to represent file-system paths.

- Save intermediate files in parquet (

.parquet) format when possible.

In general, we follow these 10 simple rules for reproducible computational research.

3. Sharing code

Sharing code is essential to extend the impact of your scientific discoveries. We write code to discover biology in our own data, and, so that others may apply our code to their own biological questions. One of our software missions is to enable others to easily repurpose our code. This mission requires working and understandable code with good repository organization. This mission also requires us to write code with open science principles (immediate open access with permissive open source licenses). For licenses, we typically use CC0 for data, BSD 3 Clause for Software, and CC-BY for analyses. We also need a venue for code sharing that we can easily build upon.

We use github to version control and share code. Our github organization is located here: https://github.com/WayScience. Each project requires a new repository, which requires a name. Naming is one of the hardest things to do in computer science, but it is also one of the most important aspects. Names are descriptive, conveying a lot of information in a few words. The original producer of the work has naming rights, but the PI has veto rights. Always discuss with the PI names for your projects.

There are three categories of github repositories, each with specific design patterns: 1) Software, 2) Analysis, 3) Data. We share these repositories similarly, with some distinctions. See our Github Strategy for complete details.

4. Reviewing code

Reviewing code (and other science bits) and providing feedback are essential skills for biomedical data scientists. If we are able to give and receive feedback well, then our growth and improvement as scientists will accelerate. By reviewing code, we learn how to effectively communicate, how to provide constructive feedback, and even learn new approaches and technologies. By having our code reviewed, we will benefit from more people understanding our project, potentially learn new approaches, and are more likely to hold ourselves to high standards. As with most things in life, diverse perspectives shared and received with respect lead to improved outcomes.

Reviewing code can be tricky. It is important to understand someone else’s code and goals, but also to let their own style shine through their work. We strive for individuality, understanding, and accuracy, so if you are able to spot a bug (or the potential for one), please highlight in a concise review.

Code review checklist

-

Do you understand the code’s intention?

-

Do you understand the code’s implementation?

-

Do you understand the programmer’s goals and concepts?

-

Is there a high potential for the code to break in the future? For example, are there hard-coded variables? Are there undefined variables inside functions?

-

Is the jupyter notebook sequentially executed? Is the nbconverted .py file up to date?

-

Is the code blacked (formatted to our style guidelines)?

-

Are there sufficient comments?

-

Does the python code comply with PEP8 standards?

-

Is there excessive repeated code?

5. Having your code reviewed

Having someone else look at your code can be scary and intimidating!

The Waylab PI (Greg) will review your first couple pull requests to ease you into this process. However, with the lab growing and projects expanding, lab-wide pull requests are necessary.

Work with Greg to find a pull request buddy, who will quickly become an expert on, and a cheerleader for, your project.

Alternatively, post your pull request in the pull-request-review Discord channel.

Please make your pull requests easy to review. They should be concise, clearly documented, and only change a minimum number of topics (ideally, 1 core change per PR). An easily reviewable PR makes review fast and speeds our science. The better your pull request is formatted, the faster it will be to review!

Remember that the scientist reviewing your PR is not an expert on your project like you are. When they make a comment or a suggestion, it does not necessarily mean that you automatically have to make the change. If you have a disagreement, clarify their question and clearly delineate your point of view. In almost 100% of cases, you and the reviewer will come to an agreement about how to move forward. Remember that our goal is to improve the project.

All code must be reviewed (and approved) prior to merging into any WayScience repositories.

Please provide a discussion for each pull request comment, within reason. For any questions or for settling any disagreements, please discuss with Greg.

6. Large refactors

Sometimes it is necessary to refactor a large amount of code, such as a pipeline. While small PRs merged into a repository’s main branch may break other parts of the repository (ex: changing code at the beginning of a pipeline will break later steps), one large PR is often too complex and large to be efficiently reviewed (see Having your code reviewed). In this case, it is a good idea to split the refactor into “chunks of change” with GitHub branches.

The methodology is as follows:

-

Create a new branch from main for the entire refactor

-

Create a new branch from the entire refactor branch for a specific change

-

File a PR from this change-specific branch into the entire refactor branch

-

Someone will review your PR and after approval…

-

Squash merge the change-specific branch into the entire refactor branch

-

Repeat 2-5 for all “chunks of change”

-

Finally, once all the changes are introduced, file a PR from the entire refactor branch into main!