playbooks

GitHub Strategy

Sharing resources is fundamental to advancing biomedical research. We share code, software, analyses, results, and data (or data access instructions) using Github. Our Github page is here: https://github.com/WayScience

We use several principles when creating, contributing to, and sharing github repositories. Each of these principles are slightly different depending on the kind of github repository. There are three categories of github repositories, each with specific design patterns:

-

Software

-

Analysis

-

Data

We will outline each of the three below.

For each repository, we practice “pull request peer review”, which we also outline below.

1. Three different kinds of Github repositories

1. Software repository

When people think about github, they usually think about open source software packages. The lab often produces individual pieces of software that we and the community use as tools. We follow standard procedures when writing software packages including:

-

Language-specific file structure and organization

-

Portable to packaging engines (e.g. pip, conda)

-

Maximal test coverage with continuous integration (using GitHub actions)

-

Consistent functional API

-

Well-documented README introducing the software

-

Full auto-doc generating a complete read-the-docs page (e.g. sphinx)

-

Gallery outlining example use cases

Examples: pycytominer, coSMicQC

2. Analysis repository

As biomedical data scientists, analysis repositories are the most common type of repository for our group. When most people think about a github repository, they are likely not thinking about storing a reproducible analysis. Nevertheless, this approach is gaining in popularity.

An analysis repository contains a collection of analyses linked together by the name of the project, which should be descriptive of the specific set of interrelated hypotheses.

Analysis repositories contain numbered folders, or modules, that have a sequential relationship. For example, the first step in most analysis repositories is data access. Therefore, the first module is often called `0.download-data`, and it contains instructions on how to access the data you use in your analysis. The subsequent modules all use these data in various ways; often exploring the data or testing various hypotheses. We also include code for generating all publication quality figures as the last module.

We use software libraries in these analyses, and we save specific versions in conda environment files or docker containers.

We also must specify the license, present a clear README with reproducibility/usage instructions, a brief summary of the results, and citation instructions.

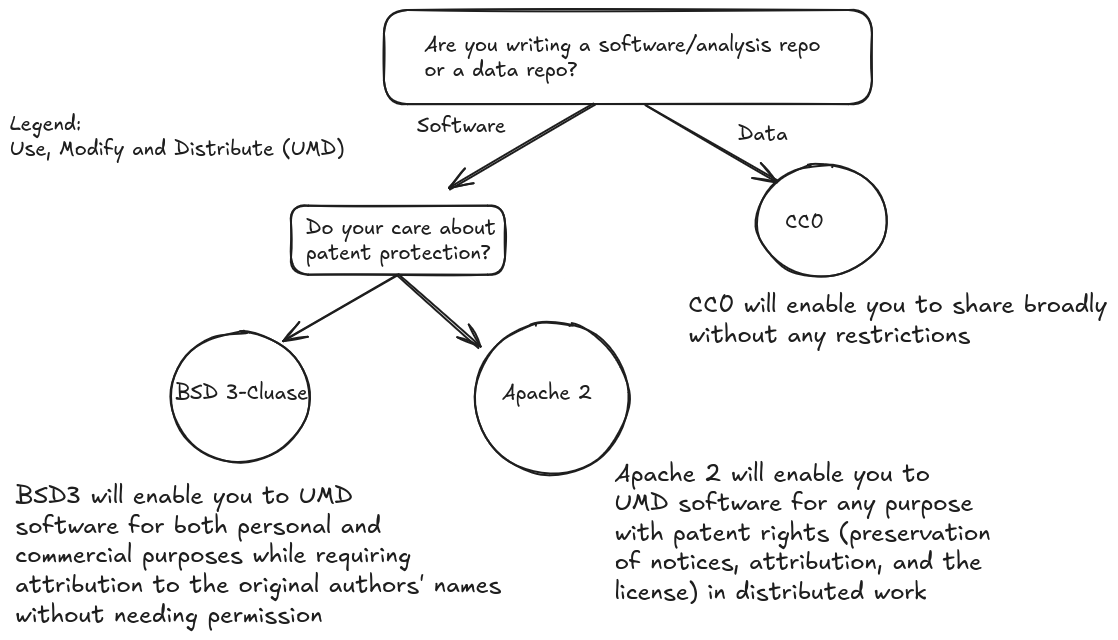

We suggest following the flowchart below to choose a license when creating a repository:

According to the CU Innovations office when creating or modifying a license you must include the following line (with the appropriate year):

According to the CU Innovations office when creating or modifying a license you must include the following line (with the appropriate year):

Copyright (c) <year> the Regents of the University of Colorado

If the copyright includes a range of years it is best practice to include this range in place of a single year: <first_year>-<last_year_developed>

For further questions about licensing requirements contact the CU Innovations Office.

To generate a license from a template in github follow this github docs guide

Analysis repositories must be included in our publications, and we consider them to be the ground truth methods section. The analyses must be fully reproducible (we aim for Gold Reproducibility) and open source. For each submission and subsequent resubmission, we generate specific “github releases”. We generate direct object identifiers (DOI) for these releases using Zenodo (instructions). We do not restrict ourselves to the one-repository per-paper strategy, instead, we opt for the one-release per-submission strategy (which can span multiple publications).

Examples: phenotypic_profiling_model, gene_dependency_representations

3. Data repository

In many projects, we collaborate with labs that generate data directly, and it is up to us to apply bioinformatics pipelines to generate analysis-ready data. We also often re-analyze existing, publicly available data (e.g. the resources on Image Data Resource). In these cases, we use a third github repository design: A data repository.

The data repository contains two key elements: 1) A bioinformatics pipeline, or recipe, of all computational steps applied to the data and 2) the data, or pointers to the data. We strive to release all of our bioinformatics steps and data publicly so that others (and ourselves!) can benefit. We believe that version controlling both our pipeline and data is essential for reproducibility, and so that we (and others) understand exactly what steps generated all intermediate files. We also make sure that this link between the pipeline and data is itself version-controlled, so that data processing steps do not lose sync in re-analysis.

This process ensures that our data can be easily reprocessed by updated bioinformatics methods with new and improved methods.

Examples from NF1 publication:

- ML and bioinformatics pipeline: nf1_schwann_cell_morphology_signature

- Data and image profiling: nf1_schwann_cell_painting_data

2. Considerations for each kind of Github repository

There are important considerations to make when creating, contributing, and sharing GitHub repositories. Table 1 below describes these considerations.

3. Github repositories as lab notebooks

We use GitHub repositories functionally as electronic lab notebooks.

4. Pull request peer review

The contributor can only merge code into WayScience (or affiliate [e.g., Cytomining]) repositories after it is approved by at least one Way lab arborist. ✅

This process has many direct and indirect benefits.

Direct benefits of pull request review

-

Only high-quality, understandable code exists in the WayScience GitHub organization.

-

We minimize future pain involved with perpetuating bugs over time (i.e., technical debt) which will lead to inaccurate or misleading interpretations.

- While pull request review slows progress in the short term, the added benefits of sustainability more than make up for this time lost in the long term.

Indirect benefits of pull request review

To the scientist writing the code (the writer)

-

Adds accountability, which encourages higher quality and more accurate analyses.

-

Encourages committing early and often, which reduces the chance of unintentional code deletion

To the scientist reviewing the code (the reviewer)

-

Adds accountability, which also encourages higher quality work.

-

Learning something new and upgrading their skills.

-

Remaining up to date on the progress of the project, which increases collaboration and comradery in the Lab.

Step-by-step process

-

The writer files a small, bite-sized pull request 🪥

-

This happens from a cloned fork of the WayScience repository

-

The smaller the better; it is WAY easier to review if small

-

-

Agentic PRs: If a pull request is created by a non-human actor (e.g., an agent or LLM model), treat it as a human-authored PR for review purposes. The person who initiated the agent action is considered the author (alongside the agent) and the PR still benefits from outside review by others. One outside approval is still required for merging.

-

The writer adds details to the pull request in markdown format

-

Justifies the rationale for why the pull request exists

-

[Optional] Encourages the reviewer to pay particular attention to any aspect

-

If the pull request contains a figure, add the figure

-

-

The writer posts a link to the pull request to the #pull-request-review discord channel

- Often, the writer knows who should take a look. Tag this person.

-

The reviewer will see the post on the discord channel and determine if they can (and are suitable) to review

- The reviewer can post to the discord channel claiming the review

-

The reviewer will review the pull request

-

Review with the desire:

-

A) understanding

-

B) to improve your peer’s code

-

C) accuracy, in this order

-

-

Review to pass along tips along any of the above axes

-

Note: Standards change over time, and we set our own standards internally. We do not prescribe a standard beyond the three items above.

-

-

The reviewer will submit their review

- This review may, or may not, include an approval ✅

-

Regardless of approval, the writer will respond to the reviewers comments (if there are any), and a discussion may ensue.

-

Note: Most often, the writer is the project owner. This means they have final say in what changes are incorporated.

- In rare cases, if there is a disagreement that cannot be resolved, involve the PI.

-

-

After approval, the writer will squash+merge the pull request into main

| Software | Analysis | Data | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Creating | Name | Up to the primary developer, PI has veto power | Up to the primary developer, PI has veto power | Descriptive of the project, typically the project is named well before the data are collected |

| Location | Most often lab org | Lab org | Lab org or pre-defined by project scope | |

| Initial files | README.md, LICENSE.md, CONTRIBUTING.md, CODE_OF_CONDUCT.md | |||

| Contributing | Location | Fork of matching lab repo, in specific feature-named branches | ||

| Tests | Maximal code coverage and continuous integration with Github Actions | Encouraged for critical analysis code used over and over again | Not required; software tested elsewhere, all pipeline steps reviewed and intermediate data tested in other repos | |

| Code review* | Limit changes per pull request (e.g. one core change); at least one approval required by project maintainer prior to pull request merge or as described in repo contributing guidelines | One analysis (or less) per pull request; one approval by lab member (or collaborator) required | One approval by a lab member (or collaborator) required. Try to keep contributions per pull request small | |

| Adding files | Everything from feature-name branches; Limit large files and do not include them in distributions | Everything from feature-name branches; Depending on size, see Data Strategy | ||

| Adding dependencies | Limit dependencies, add specific version(s) to requirements file | Limit dependencies, add specific version to environment file | Only pipeline and standard data visualization/exploration software | |

| Organization | Standard package organization | Module-based sequences that depend on prior steps | Store critical intermediate data in different forms, or, if too large, include access instructions | |

| Sharing | Version control and citable code | Maintain version on common package installers (e.g. pip, conda); include citation instructions | Mint a DOI using zenodo per release; Github releases track paper submissions | Mint a DOI using zenodo per release; Github releases track full pipelines |

Table 1: Creating, contributing, and sharing software, analysis, and data repositories. *See details on code review below

Using GitHub as a Web Host (GitHub Pages)

GitHub provides the ability to host web pages through a feature called GitHub Pages.

Websites built with GitHub Pages are generally considered “static sites”.

By default, GitHub Pages uses the Jekyll static site generator.

You may also configure other static sites by using the .nojekyll file at the root of your GitHub Pages content.

Configuring GitHub Pages with Defaults

- Go to your repository on GitHub.

- Ensure there are markdown (

.mdfiles) within the root of the repository (for example, areadme.mdfile). - Click on the “Settings” tab (located near the top of the repository).

- Scroll down to the “Pages” section.

- Under “Branch,” select

main(or your default branch) from the dropdown, and leave the folder as/root. - Click “Save” and GitHub Pages will be enabled using the defaults (note: it takes a few moments for the initial deployment and URL to appear after this).

Your site will be live at https://<username or organization>.github.io/<repository-name>/.